|

Domus Aurea To introduce this page I am going to quote information from the Wikipedia which gives a brief history of Nero's Golden House, following this is a text from an Exhibition catalogue which explains the history of one of the most important publications to have even been produced concerning the frescoes found at Domus Aurea. |

|

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia "The Domus Aurea (Latin, "Golden House") was a large landscaped portico villa. Designed to take advantage of artificially created landscapes, Domus Aurea was built by the Emperor Nero in the heart of ancient Rome, after the great fire in 64 AD had cleared away the aristocratic dwellings on the slopes of the Palatine Hill. Built of brick and concrete in the few years between the fire and Nero's suicide in 68, the extensive gold leaf that gave the villa its name was not the only extravagant element of its decor: stuccoed ceilings were applied with semi-precious stones and ivory veneers, while the walls were frescoed, coordinating the decoration into different themes in each major group of rooms. Though the Domus Aurea complex covered parts of the slopes of the Palatine, Esquiline and Caelian hills, with a man-made lake in the marshy bottomlands, the estimated size of the Domus Aurea is an approximation, as much of it has not been excavated. Some scholars place it at over 300 acres (1.2 km2), while others estimate its size to have been under 100 acres (0.40 km2). Suetonius describes the complex as "ruinously prodigal" as it included groves of trees, pastures with flocks, vineyards and an artificial lake - rus in urbe, "countryside in the city". The Golden House was designed as a place of entertainment, as shown by the presence of 300 rooms without any sleeping quarter. Nero's own palace remained on the Quirinal Hill. Strangely, no kitchens or latrines have been discovered yet either. Rooms sheathed in dazzling polished white marble were given richly varied floor plans, shaped with niches and exedras that concentrated or dispersed the daylight. There were pools in the floors and fountains splashing in the corridors. Nero took great interest in every detail of the project, according to Tacitus' Annals, and oversaw the engineer-architects, Celer and Severus, who were also responsible for the attempted navigable canal with which Nero hoped to link Misenum with Lake Avernus. Some of the extravagances of the Domus Aurea had repercussions for the future. The architects designed two of the principal dining rooms to flank an octagonal court, surmounted by a dome with a giant central oculus to let in light. It was an early use of Roman concrete construction. One innovation was destined to have an enormous influence on the art of the future: Nero placed mosaics, previously restricted to floors, in the vaulted ceilings. Only fragments have survived, but that technique was to be copied extensively, eventually ending up as a fundamental feature of Christian art: the apse mosaics that decorate so many churches in Rome, Ravenna, Sicily and Constantinople. Nero, who was obsessed with his status as an artist, certainly regarded entertainments as works of art. His official arbiter elegantiarum, or judge of elegance, was the novelist and courtier Petronius. Frescoes covered every surface that was not more richly finished. The main artist was one Famulus (or Fabulus according to some sources). Fresco technique, working on damp plaster, demands a speedy and sure touch: Famulus and assistants from his studio covered a spectacular amount of wall area with frescoes. Pliny, in his Natural History, recounts how Famulus went for only a few hours each day to the Golden House, to work while the light was right. The swiftness of Famulus's execution gives a wonderful unity to his compositions and astonishing delicacy to their execution. Pliny the Elder presents Amulius as one of the principal painters of the domus aurea: "More recently, lived Amulius, a grave and serious personage, but a painter in the florid style. By this artist there was a Minerva, which had the appearance of always looking at the spectators, from whatever point it was viewed. He only painted a few hours each day, and then with the greatest gravity, for he always kept the toga on, even when in the midst of his implements. The Golden Palace of Nero was the prison-house of this artist's productions, and hence it is that there are so few of them to be seen elsewhere." The Domus Aurea still lies under the ruins of the Baths of Trajan and the surrounding park. After Nero's death, the Golden House was a severe embarrassment to his successors. It was stripped of its marble, its jewels and its ivory within a decade. Soon after Nero's death, the palace and grounds, encompassing 2.6 km? (c. 1 mi?), were filled with earth and built over: the Baths of Titus were already being built on part of the site in 79 AD. On the site of the lake, in the middle of the palace grounds, Vespasian built the Flavian Amphitheatre, which could be reflooded at will, with the Colossus Neronis beside it. The Baths of Trajan, and the Temple of Venus and Rome were also built on the site. Within 40 years, the Golden House was completely obliterated, buried beneath the new constructions, but paradoxically this ensured the wallpaintings' survival by protecting them from dampness. Renaissance When a young Roman inadvertently fell through a cleft in the Esquiline hillside at the end of the 15th century, he found himself in a strange cave or grotta filled with painted figures. Soon the young artists of Rome were having themselves let down on boards knotted to ropes to see for themselves. The fourth style frescoes that were uncovered then have faded to pale gray stains on the plaster now, but the effect of these freshly rediscovered grottesche decorations was electrifying in the early Renaissance, which was just arriving in Rome. When Pinturicchio, Raphael and Michelangelo crawled underground and were let down shafts to study them, carving their names on the walls to let the world know they had been there, the paintings were a revelation of the true world of antiquity. Beside the graffiti signatures of later tourists, like Casanova and the Marquis de Sade scratched into a fresco inches apart (British Archaeology June 1999), are the autographs of Domenico Ghirlandaio, Martin van Heemskerck, and Filippino Lippi. It was even claimed that various classical artworks found at this time - such as the Laocoön and his Sons and Venus Kallipygos - were found within or near the Domus's remains, though this is now accepted as unlikely (high quality artworks would have been removed - to the Temple of Peace, for example - before the Domus was covered over with earth). The frescoes' effect on Renaissance artists was instant and profound (it can be seen most obviously in Raphael's decoration for the loggias in the Vatican), and the white walls, delicate swags, and bands of frieze - framed reserves containing figures or landscapes - have returned at intervals ever since, notably in late 18th century Neoclassicism, making Famulus one of the most influential painters in the history of art. Vestigia delle Terme di Tito From Nero's Golden House Exhibition organised to commemorate the 200th death anniversary of Franciszek Smuglewicz Text from the catalogue of the exhibition translated by Justyna Woldanska This folio sized volume contains sixty large hand-coloured plates showing paintings from the basement of an ancient building taken for the Baths of Titus (Thermae Titi), which in fact were the ruins of Nero's Golden House (Domus Aurea). This great work of art was created by Vincenzo Brenna, a Roman architect (17451820), a Polish painter and draughtsman Franciszek Smuglewicz (17451807), and Marco Gregorio Carloni (17421786), a Roman engraver specialising in engravings of ancient monuments. The portfolio Vestigia delle Terme di Tito was created in Rome as a result of excavations commissioned by an entrepreneurial paintings dealer Ludovico Mirri, whose shop was situated near Palazzo Barberini. Having attained a hard to get privilege from Pope Pius VI, Mirri began his work in the Baths of Titus in 1776. The excavation was done at a great pace for that period, and Mirri hired Smuglewicz and Brenna to document the results. Already two years later the coloured version was ready. Mirri himself announced that it should be treated as an original work of art: each of the sixty plates was hand-coloured on an extremely delicate etching outline in light sepia. This etching outline was made with different plates than the black-and-white etching version, which can be judged not only on the basis of Mirri's assertions, but also on the basis of numerous dissimilarities between the coloured and the black-and-white versions. The latter, published in a much larger number of copies, is kept in the majority of large European libraries which existed already in the 18th century. The coloured version was intended for the wealthiest collectors, Antiquity lovers and experts because of its very high price of 180 sequins in gold in subscription and 200 for the whole portfolio. Complete copies can be found in only a few European collections (Louvre Museum, Paris, Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest, The Royal Collection at Windsor Castle Windsor, The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, National Museum in Warsaw). The black-and-white subscription version had an academic commentary of Giuseppe Carletti, a Roman erudite and poet, who explains the subjects and iconography of the individual plates referring to prior sources and interpretations. The Baths of Titus, excavated in 1776, were already known much earlier. The paintings decorating the Baths were unearthed for the first time by accident in the 1470s, when they became an inspiration for grotesques, that is decorative motifs named after the place of their discovery (Italian grotta means "a cave"). Raphael was the creator of modern grotesques, and the Loggias of the Vatican, where they appeared, were such a perfect work of art that they constituted an unparalleled example for more than two centuries. The 17th century brought a development of research into Roman art understood as the source of knowledge about ancient history and customs, which lead to the fact that, unlike in the Renaissance, artists were more interested in figural decoration. Therefore, figural motifs in the mosaic of Palestrina, the frescoes of the Pyramid of Cestius, and above all the Aldobrandini Wedding discovered at that time aroused admiration. The fame of the latter was not even dimmed by historic discoveries made in the next century. The discoveries in Herculaneum and their popularisation through a multi-volume edition Antichita d'Ercolano Esposte favoured further search, also in the Baths of Titus. Despite the difficulties in obtaining the Pope's privilege entitling to carry out excavations, in the second half of the 18th century they were conducted twice: in 1772 by a Scottish architect Charles Cameron, and two years later by Ludovico Mirri. However, the passage of time had such an effect that not all paintings known in Raphael's times were equally clearly visible, and although Brenna and Smuglewicz could examine them closely while working under the ground for months, they were forced to refer on many occasions to earlier iconographic sources. The unearthed rooms, due to the lack of windows and a dark tone of some paintings, were considered by the contemporaries as the Baths of Titus, whereas in fact they were the interiors of Nero's Golden House, which became forgotten and buried as fast as it was constructed, and it served as foundations of the Baths of Titus, and later the Baths of Trajan. The attitude towards the paintings in the Golden House was greatly influenced by their role as a source of inspiration to Raphael, whose decoration of the Loggias of the Vatican was transferred to prints in a great graphic work of Giovanni Volpato in 1772. While comparing the Loggias of the Vatican and Vestigia delle Terme di Tito one can notice how their authors evolved from documentation to invention. Brenna, Smuglewicz and Carloni created an unusually convincing picture of Roman painting, far from the so-called late-antique "Impressionism". Their vision matched the tastes of their epoch - the aesthetics of neoclassicism emerging then in the international artistic circle of Rome. This is especially visible in the so-called quadri, namely large figural compositions by Smuglewicz. The young Pole came to Rome in 1763 and was clearly fascinated by ancient art, earlier unknown to him, and as befitted a man from the North, he perceived it with an enthusiasm far greater than Brenna, born and educated in Rome, where the classical tradition was everlasting. Both artists socialized in cosmopolitan circles of the Eternal City in times of Grand Tours, where young men (mainly English, but also the above-mentioned Stanislaw Kostka Potocki) from the best families, had the opportunity to come into contact with Antiquity researchers and collectors, experts and artists, whom they often hired as draughtsmen, documentalists, designers, art agents. It was that way in the case of Smuglewicz, who, as Anton von Maron's student, was soon (1765) to work for a Scottish collector and Antiquity lover James Byres, for whom he successfully documented Etruscan tombs discovered not much earlier in Corneto and Tarquinii. Similarly, Brenna met Potocki and worked for him in Rome, and later went with him to Poland. |

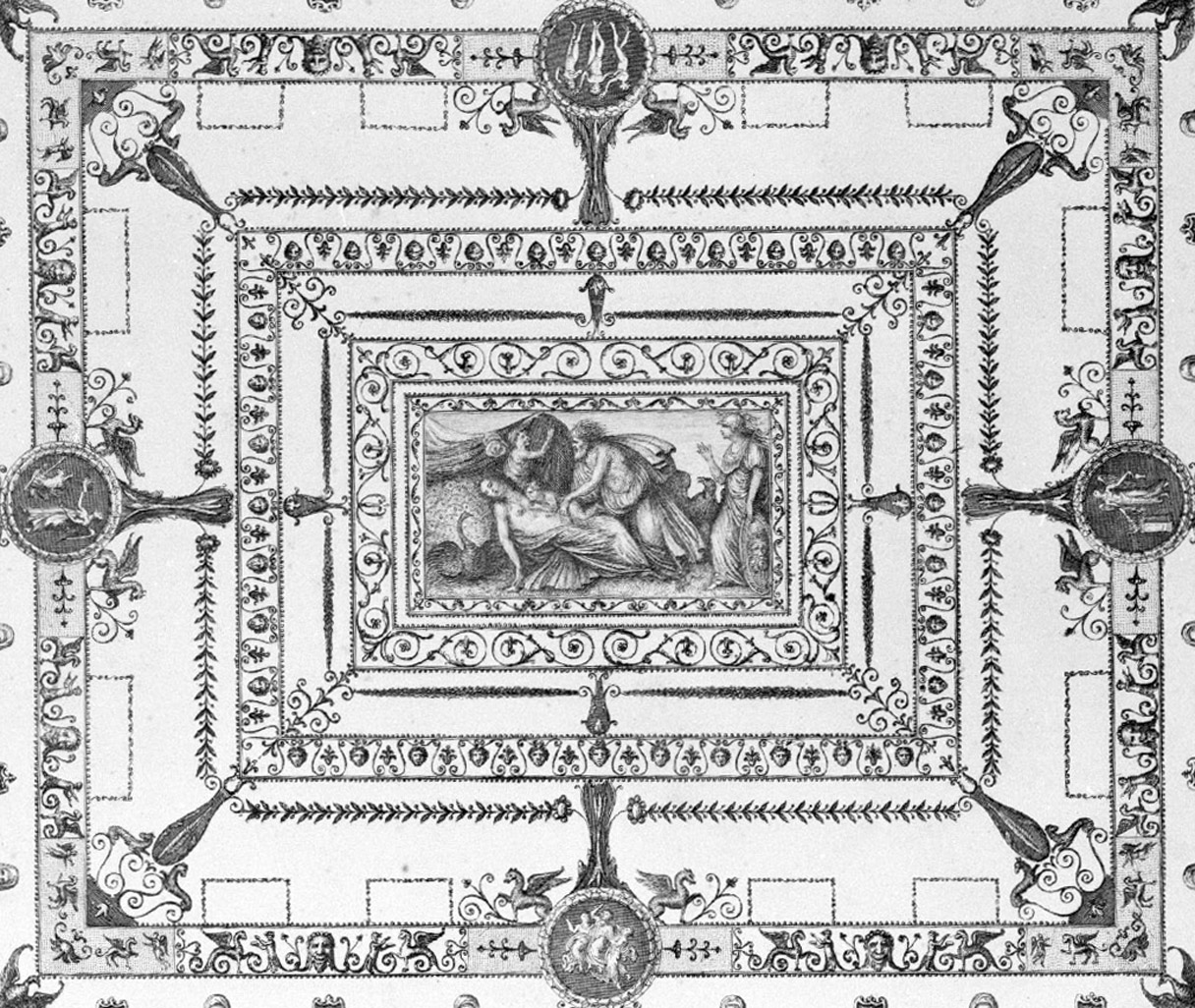

| We have been exploring the history of acanthus frieze as an element docoration in the remote past, coincidentally candelabra motifs appear to accompany the acanthus into antiquity. Now we are journeying back 2000 years to look at Roman wall painting. The acanthus frieze that I show at the bottom of the previous page is found in Plate 24 of the Domus Aurea engravings by Vincenzo Brenna, Franciszek Smuglewicz, Marco Gregorio Carloni, Vestigia delle Terme di Tito e loro interne pitture. Rome.) Let us explore some of these plates together. First I want to show plate 6, which is the first to cover a multitude of diverse subjects and decoration. I have found a smallish copy of the color plate as well as a larger black and white copy. The complete collection of the the black and white plates can be downloaded here at www.bildindex.de. |

| We can see in the photograph above, the same general dispersal of decoration and enclosed paintings as observed in plate 6. This photograph appears to be a rare picture of the few remaining well preserved frescos at Domus Aurea. Now after hours of pouring over photographs and engravings from diverse sources, I am forced to conclude that a large part of plates from the 1776 publication Vestigia delle Terme di Tito e loro interne pitture. are not true copies of the Domus Aurea wall paintings. They are composite arrangements of various details that have been assembled to produce symmetrical well ordered illustrations. In doing this they have compromised all their efforts to bring to the public an authentic representation of what they observed. While it is probably true that the individual paintings within the decoration may have been accurately represented in their engravings, the decoration itself has been invented in the general style and patterns of the motifs that they recorded. |

| In Comparative Diagram 1, I show Plates 28 and 46, the decorative frieze is identical in both plates, this would never occur in reality, even if the frieze was of this kind many differences would appear either through error or design. On the the next page we are going to look at more of these plates, and discover something even more mysterious and disturbing. |